DOCTOR WHO

THE LEGACY COLLECTION

DVD

RRP: £30.63

BBFC: PG

RRP: £30.63

BBFC: PG

Released by: BBC Worldwide

Release date: 7 January 2013

"K9, you can come along, but no tangling with any Krargs – unless, of course, you have to tangle with any Krargs"

A great

number of Doctor Who stories have

been cancelled before they entered production, but there is just one where

shooting was stopped in its tracks part-way through: Shada. It is this story

which the first two discs of The Legacy

Collection, the first Doctor Who

DVD release of 2013, are dedicated to. Intended to end Season Seventeen in

1980, the story fell victim to industrial action and was never completed.

If writer

and script editor Douglas Adams had his way, he wouldn’t have written it in the

first place. Adams had two story ideas in mind, one in which the Doctor

retires, and the other involving cricket (more details on those in this DVD’s

subtitle production notes). But producer Graham Williams put his foot down on

both, so Adams came up with a cunning plan. If he didn’t write anything else,

with the deadline rapidly approaching, Williams would have to give in! Except,

he didn’t. There was no way he was going to give either of Adams’ ideas the

green light, so the writer ended up having to script Shada in a matter of days. As he once said, “I love deadlines. I

love the whooshing noise they make as they go by.”

The story

revolves around the most dangerous book in the universe, which was brought from

Gallifrey to Cambridge by retired Time Lord, Professor Chronotis (Denis Carey).

What we have of Shada is all of the

location filming, plus one of the three planned studio recording blocks. Looking

at the material that was shot, this would have been a story very much of its

era, with a whole host of gags – some of them inserted by the cast (in

particular, Tom Baker), and the others… well, with Adams writing, what do you

expect? The location work in and around Cambridge and its university – where

Adams himself studied – is luxurious (with Baker getting the chance to both

punt on the River Cam and engage in a manic bicycle chase sequence), and

certainly the best of what was recorded, with a certain relaxing charm to it. Thankfully,

a small portion of the location footage was used to represent the Fourth Doctor

in the 1983 twentieth anniversary special The

Five Doctors, after Baker declined to take part. It was during the shooting

of the location scenes, though, that problems started to arise. The long chase

scene was originally intended to take place at night, but a strike was called,

meaning that the lighting crew were unable to work. So, the sequence was

hastily re-worked for daytime shooting. The combination of the location

material and the fully completed first studio block means that the first two or

three episodes are fairly well represented, but the second half of the story is

where the gaps get larger and larger.

The real

question is this: as a story, is Shada

actually any good? The beginning sets up a grand tale of exploration into the

secrets of the Time Lords, but as it progresses, it does seem as though the

story thins out – not just in terms of the footage that exists, but also of the

amount of incident in the plot. But we’ll never truly be able to tell what Shada would have been like if it had

been completed in 1979, although it undoubtedly receives more attention now

that it ever would have done if it had been finished (Adams himself didn’t

think much of his own story, due to the constraints under which it was written).

In the material that we do have, though, the cast is on fine form. Series

regulars Tom Baker and Lalla Ward had great on-screen chemistry by this point, and

this goes hand-in-hand with Adams’ dialogue. At this time, Baker was playing

the Doctor as an outwardly whimsical character, with moments of intense

gravitas and power. While this often leads him to go slightly too over-the-top

in Season Seventeen, the balance is much better in Shada. The exchanges between the Doctor, Romana and Chronotis positively sparkle, and are just delightfully silly. But when the Doctor discovers exactly which Gallifreyan book

the Professor has lost, Baker’s performance changes in a heartbeat.

Ward adores

anything and everything with Adams’ name on it, and has often cited having her

name in the same credits sequence as him as a highlight of her career. So, it’s

no great surprise that she is clearly revelling in Adams’ script. Romana

frequently managed to escape the cliché of the Doctor Who companion, because being a Time Lord, she was at an equal

intellectual level to the Doctor himself. Indeed, there is a scene later on in Shada in which Romana effectively comes

up with the solution to the entire story, and it’s played by Baker and Ward

with wit and affection. In Season Seventeen, K9 was played not by John Leeson,

but by David Brierley. While Brierley’s performance is very far away from the

voice we commonly associate with the robot dog, it has a character all of its

own (and was explained away in-universe by K9 contracting laryngitis). K9 takes

a while to get in on the action in Shada,

but after he finally trundles out of the TARDIS, he is the centrepiece of some

amusing moments, in addition to being the preacher of exposition that he

usually is. Brierley actually returned in 1992 to voice K9 in one film scene

which hadn’t been dubbed when Shada

was abandoned, and it does seem as though his laryngitis gets worse in that one

scene…

Denis Carey

makes Professor Chronotis one of my all-time favourite Doctor Who characters. Chronotis could be seen to reflect the

Doctor himself in this season of the programme – he largely appears to be a

bumbling, forgetful old man, but while his air of eccentricity never leaves

him, he proves in certain scenes that he is far more alert and clever than he

appears. Carey plays the part with such dynamism, mystery and enthusiasm that

he is fascinating to watch in the scenes that exist. It’s marvellous that all

of the scenes in Chronotis’ rooms were completed. One good thing that came out

of the cancellation of Shada was that

Carey was then able to appear in another Doctor

Who story the following year, as the eponymous Keeper of Traken. Chris

Parsons (Daniel Hill) and Clare Keightley (Victoria Burgoyne) are frustrating

as characters, because there’s a lot of untapped potential there.

Unfortunately, they seem to be here only to serve functional purposes in moving

the plot along. There’s no real character depth to them, and the presence of

the Professor (who does have

interesting layers as a character) only makes this all the more obvious. When

Gareth Roberts novelised the story in 2012, he fixed this problem and

added a romantic touch to the relationship between Chris and Clare. Watching

the original 1979 production, it feels very much like the same romance should

be there, but it isn’t. When writing his novelisation, Roberts said that it

looked like Adams intended to flesh out the two characters, but he had run out

of time before he could do so. Watching what there is of Shada, I can only agree. Chris and Clare are interesting as

‘almost-companions’, but they could and should have been a lot more interesting

in their own right. Fortunately, Hill and Burgoyne do their best with the

material they have – Hill plays Chris with a brilliant awkwardness, and

Burgoyne counters this with a simultaneous sense of fondness and annoyance towards him.

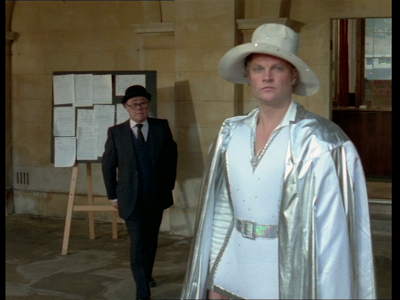

There is one

character, though, who suffers hugely from the missing scenes: the villain of

the piece, Skagra (Christopher Neame). It’s quite possible that he would have

been a very interesting enemy if Shada

had been completed, but annoyingly, the vast majority of the scenes which might

well have elevated Neame to greatness are among those which weren’t committed

to tape. This includes the revelation of what Skagra’s grand plan actually is (which

is relegated to Baker’s narration here), so the footage that exists of Skagra

essentially consists of him walking around in the campest costume in the

cosmos, with lots of people asking “Who are you?” and “What do you want?”,

without a satisfactory reply ever being received. There’s just no context to

anything that’s going on, and while this is obviously true for the whole story

to an extent, Skagra suffers most profoundly of all.

The version

of Shada that is included on this box

set is the same one that was first released on VHS in 1992, with in-vision

links and voiceover by Tom Baker (written by John Nathan-Turner, producer of Doctor Who for almost all of the 1980s

and the man at the helm of the 1992 video release) to attempt to bridge the

gaps. This has never been a hugely satisfactory way to watch the story, though.

The opening introduction is certainly a fun, witty example of Baker at his best

(“Beat you, cock!”), but the narration of the missing scenes has a problem from

the beginning, which only gets worse as the story progresses. Namely, the links

are often no-where near detailed enough. They just about allow the first half

of the story to be followed (the first episode has the same running time as a

full episode, in fact) but in the second half (as the existing material rapidly

diminishes, and the balance tips so that the narration has the responsibility

of telling most of the story) it gets to the point where huge chunks of

dialogue and action are condensed into links which are usually too short to do

the material justice. When the climactic showdown arrives, which went entirely

unrecorded in 1979, it’s very difficult to properly comprehend – what would

have been a very visual set-piece is instead converted into a series of very

fast descriptions. Another example of a part of the story which suffers is the

cliffhanger to Part Three, which is a fantastic piece of writing by Adams in

the script, but is condensed into just a few words in the narration.

At the time

of the story’s cancellation, not only was a lot of material left unrecorded,

but even the existing footage wasn’t truly finished. Perhaps the most notable

example is the music, which would originally have been provided by the series’

regular composer, Dudley Simpson (for whom, like Williams and Adams, Shada would have been his Doctor Who swansong). However, when the

production stopped, Simpson hadn’t composed so much as a single note. For the

1992 VHS, Nathan-Turner employed the services of Keff McCulloch, who arranged

the version of the theme tune used during Sylvester McCoy’s era, as well as

providing the incidental music for a number of stories during that period. McCulloch’s

music for Shada attempts to reference

the style of Simpson, and has always been very divisive among fans. Although it

certainly takes a while to get used to music of the McCoy era’s style on a Tom

Baker story, I personally feel that McCulloch’s score is actually quite

sympathetic to the era that Shada

would have been a part of. If anything, the electronic sounds used to realise the score are what sometimes let

it down – they are often too ‘late 1980s synth’. You could say that McCulloch

was playing all the right notes, but not necessarily with the right

instruments…

The film

sequences were edited back in 1979, so this material is presented exactly as it

would have been if the story was finished and transmitted. The studio

recordings, though, were left as an unedited jumble of multiple takes and

recording breaks, so the assembly of those was done from scratch for the 1992

release. It’s possible that there are better takes in existence than those used

here (there’s the odd fluffed line), but what we’ve got is all we’ve ever seen.

Only some of the effects were finished originally; others had to be made in

1992 by Ace Editing. These non-original effects are of varying quality. The

sphere keyed into the film segments is among the better of them (although you

can tell at times that it’s a still image being moved around the frame, because

of the pixelation that appears when the sphere is seen very close-up, it

nevertheless evokes the CSO feel that it would have had originally in many

shots), but the mocked-up model shots using cut-outs of freeze-frames are often utterly dire and not remotely convincing. They’re okay when they just consist

of a still photograph, but once any movement or compositing is attempted, they usually become completely risible.

There must be an overriding reason why no version of Shada other than that already released on VHS could be put out on

DVD, but the re-use of such a poor attempt to tell the story can’t help but

come as a disappointment. (I’ve always thought that animation would be the best

way to present the missing sections – whether that be Ian Levine's production or a new one by BBC Worldwide themselves – but failing that, a presentation using CGI/photographs/composited

images and extracts from the AudioGO audiobook would be an interesting idea.) When

the VHS came out in 1992, included in the box was a script book. Although they

weren’t actually the latest versions of the scripts, they at least allowed the

missing parts of the story to be followed in a manner far more satisfactory

than the video itself managed. Sadly, no such thing accompanies this DVD – it

would have been nice to see a PDF of either the same scripts or (preferably)

the latest editions included. The information subtitles partially do the job,

but more on that a little later. Theoretically, since the restoration of this

story was carried out by going back to the original film and videotape

elements, it would have been possible to take the opportunity to spruce up the

non-original effects. It would have been interesting to see this done, but the

1992 effects have been recreated instead.

SPECIAL

FEATURES

In 2003, a webcast of Shada was made available on the BBC Red Button and then online. It

used an audio adaptation of the story by Big Finish, and Flash “animation” to

tell the complete story. Tom Baker declined to participate, so Paul McGann’s

Eighth Doctor was used instead. The main problem, though, comes with the rest

of the casting. Apart from Lalla Ward as Romana, not a single other actor from

the original production of Shada

features in the audio version. Andrew Sachs replaces Christopher Neame, James

Fox replaces Denis Carey and Sean Biggerstaff replaces Daniel Hill, to name

just a few. Somehow, this

interpretation of Shada just seems lifeless compared to the original (even in its

incomplete state), and it’s too far removed from the TV version for my taste.

This adaptation makes an intriguing attempt to fit within the wider Doctor Who timeline, by using the events

of The Five Doctors to effectively

delete most of the original from history, thus giving the later incarnation of

the Doctor a reason to go and complete the adventure he was supposed to have

all those years ago.

My favourite

feature on every Doctor Who DVD is

the Production Information Subtitles.

With information about the making, cast, crew and context of the stories in

question, they are always fascinating to read. Shada’s set of subtitles (written by Nicholas Pegg) features a wealth of facts about both the

1979 and 1992 productions. Complimenting Now

and Then nicely, we learn about the geography of the filming locations (and

where it does and doesn’t match reality), and we are told where sound effects

are missing from the 1992 presentation. Speaking of which, the subtitles

include information about the various ideas which were floating around of how

to present Shada prior to 1992. But

the least said about the script’s term for the sphere’s actions, the better…

Given the

circumstances surrounding Shada, the

director’s perspective and recollections are arguably the most fascinating of

all, so producer/director Chris Chapman's use of the archive interview with Roberts is most welcome.

Production assistant Ralph Wilton has very fond memories of Roberts, speaking

of how the director was determined not to let production on Shada go under, and kept morale up

within the cast and crew. Assistant designer Les

McCallum is on-hand to talk about how the Cambridge location inspired and

provided reference for the design of some of the studio sets, and this is

especially interesting where the set in question was never recorded on. Tom

Baker is in the documentary, but his interview wasn’t shot in Cambridge.

Instead, he was interviewed – quite literally – in his own back garden. There

are many comic highlights to his contribution here (such as a dig at BBC after-parties),

but also a very interesting take on the story’s cancellation. Baker’s

description of the first studio lock-out as “the seeds of doom” is a very

concise but effective summary of the situation. Taken Out of Time is a documentary that I had been looking forward

to seeing for a long time, and it doesn’t disappoint. Indeed, it’s one of the best

features of the entire box set.

As with

every other classic Doctor Who DVD, a

Photo Gallery assembled by Paul Shields is included. At nearly

five minutes, a variety of images is included here. Some of them are familiar,

others far less so. We get at least one glimpse of a set that is never seen in

the recorded footage, along with plenty of images from the location filming (in

particular, the scene on the River Cam). This feature also provides the

opportunity to hear a selection of McCulloch’s music from the 1992 release of Shada in isolation.

"You may well think that, but I couldn't possibly comment"

In 1993,

there was no regular Doctor Who on

television. The series had ended four years earlier in 1989, and Paul McGann’s

sole outing in the TV Movie was still three years away. Initial plans for a major

direct-to-video special called The Dark

Dimension to celebrate the programme’s thirtieth anniversary had collapsed (and

what appeared instead was Dimensions in

Time, a highly questionable EastEnders

crossover skit within Children in

Need). But then, out of the dark wilderness came something amazing. 30 Years in the TARDIS was a documentary

covering the (then) entirety of the programme’s history, and it is an extended

version – More than 30 Years in the TARDIS – which appears for the first

time on DVD on the third and final disc of this box set, following its VHS

release in 1994.

Covering

over three decades of Doctor Who in just

under eighty-eight minutes must have been a mind-boggling challenge for

director Kevin Davies, but the format which the finished programme has is,

quite simply, genius. It opens with a young boy (played by Josh Maguire) running

through London, re-enacting many iconic scenes from Doctor Who (mixed with the original

clips) along the way. This use of dramatic

re-creations is absolutely inspired, and one of the reasons why this

documentary is such a love-letter to the series.

Narrated by

Nicholas Courtney, More than 30 Years in

the TARDIS is divided into three segments, each designed to look at

different aspects of Doctor Who (and

the cliffhangers bridging these are marvellous). There is certainly a lot to

explore – all of the following are touched upon at some point: the missing

episodes, the origins of the series, the enemies of the Doctor, the companions,

fashion sense (or a lack of)… There’s so much included, it’s difficult to put

it into words. Lots of archival treats are included too, including a number of

contemporary adverts – placed within ‘commercial breaks’ – involving Doctor Who. My favourites have to be the

Prime Computer ones (other calculators the size of a room are available,

though).

The striking

thing is how much everybody involved (except Mary Whitehouse) totally loves the programme. Nicholas Courtney

fondly remembers the UNIT heyday of “five rounds rapid”, Verity Lambert recalls

the genesis of the Doctor and Toyah Wilcox expresses her love for

those sexy Cybermen. Oh yes.

This documentary

is now twenty years old, but as an overview of the eras of the first seven

Doctors, it is still top of the range. There is probably a lot of unused

material sitting in Davies’ attic, and it would have been great to see some of it

(either in a re-edit of the main programme, or in a DVD extra), but even in its

existing 1994 form, it’s solid gold.

SPECIAL

FEATURES

None of the

special features on this disc relate directly to More

than 30 Years in the TARDIS. Instead, the final disc of The Legacy Collection serves as a

‘mopping up exercise’ of extras left over from elsewhere. Top billing goes to Remembering

Nicholas Courtney, a hugely touching and poignant piece about the late

Brigadier Lethbridge-Stewart actor. It mostly consists of footage from an

incomplete interview with Courtney, spanning his entire life and career. But he

became too unwell to finish the interview, and subsequently passed away in

2011. The footage that was recorded sees the light of day here, now turned into an

obituary piece by Ed Stradling. The gaps in the interview are luckily filled using other

archival interview footage. The interviewer is Michael McManus, a close friend

of Courtney and co-author of his 2005 autobiography, Still Getting Away with It. It has to be said that Courtney does

understandably look a little frail in this final interview, with makes it all

the more emotional to watch. But equally, it’s a joyous reflection on the life

story of Courtney. When a certain guest turns up, it’s a genuinely surprising

moment (even though I’d seen a photo of it months before, but it had slipped my

memory), and a very happy one at that. There are plenty of clips from some of

Courtney’s non-Who roles, as well as

highlights from his appearances as the Brigadier across many years. To call

this an obituary perhaps makes it sound too morbid, so it might be better to

call it a tribute – and what a tribute it is, to the life and work of one of

the greatest legends of Doctor Who.

Doctor

Who Stories – Peter Purves is the latest entry in the ongoing series,

using interview footage from 2003’s The

Story of Doctor Who. Purves recalls his salary when working on Doctor Who and his handful of location

filming experiences, and it seems that he still has very accurate memories of

this part of his career. As with Yentob’s contribution to More than 30 Years in the TARDIS, it’s interesting to hear Purves

speculating about the possible return of Doctor

Who (which was two years away), and how it would need to be different from

the old days. He also speaks of his preference for the historical stories

rather than the ones with monsters, and it seems that Purves especially

dislikes Daleks. He then talks about his time on Blue Peter, which continued his association with Doctor Who – particularly amusing is a

clip about the creation of sound effects. Although this series of interviews is

obviously out of date regarding the lack of any new stories on television at

that time, it remains interesting to watch, and Purves’ entry is no exception.

The

Lambert Tapes – Part One is essentially a pilot for the Doctor Who Stories series, taken from

Verity Lambert’s interview for The Story

of Doctor Who. Considering it as a part of that series for the purposes of

this review, it is one of the most captivating instalments that I’ve yet seen,

as Lambert discusses her experience jumping from being a production assistant

at ABC Television to the first female producer at the BBC. It is fascinating to

hear her story of walking into her first producers’ meeting at the BBC, and how

she felt working with some of Doctor Who’s

earliest directors. The usual graphics work by Michael Dinsdale is not present here, as

this was made before Doctor Who Stories

got going as a regular feature, and the usual music is replaced by a

slowed-down version of the original Doctor

Who theme tune, which works surprisingly well.

James Goss' Those

Deadly Divas is a good idea, but bizarrely executed in some respects. Featuring

Kate O’Mara, Camille Coduri, Tracy Ann Oberman, Clayton Hickman and Gareth

Roberts, it’s a look at the power-hungry females who have appeared in Doctor Who over the years. From the Rani

to Captain Wrack, Krau Timmin to Tegan as the Mara, there are lots of brilliant

characters discussed, but in places the construction seems a bit odd. The

feature is divided into a number of sections, when it doesn’t really need to be

– the character-by-character approach would have sufficed on its own, without

dividing it further into numerous strange categories that don’t actually mean a

great deal. Then there’s the intrusive singing by the Wire (The Idiot’s Lantern) at the beginning of

each new section, which grates after a while. But the interviewees have some

excellent things to say, and O’Mara makes every syllable she utters

interesting. The shadow puppet graphics feature again as well (but in a very

different style), which is always a winner.

Another Photo Gallery from Paul Shields is featured, with a

selection of photos from the production of More

than 30 Years in the TARDIS. This is the first time that such a gallery has

ever been produced for anything that isn’t a Doctor Who story, and there are some fantastic shots included,

ranging from Jon Pertwee in the Whomobile to a Draconian in make-up. Some of

Mark Ayres’ brilliant music from the documentary is used to score the gallery.

Included in

the form of a PDF file is a cutting from an issue of Radio Times, listing 30 Years in the TARDIS within that day’s

programming schedule. It’s always fun to read these, but it’s perhaps a shame that the

opportunity wasn’t taken to present the ones that weren’t included with stories

from much earlier in the DVD range.

Finally,

there is an Easter Egg to be found

somewhere on the menus of this disc – a lovely clip which links with another

special feature…

AUDIO/VIDEO

Everything sounds

fine on both Shada and More than 30 Years in the TARDIS. The

music in the former has come out of Mark Ayres' restoration process sounding less tinny

than it did on VHS, which is most welcome, and there are no issues to report.

The

transformation in Shada’s visual

quality for this release is outstanding. The whole thing has been

rebuilt from the studio recordings and 16mm film negatives, and it looks marvellous

as a result. The studio sections look a lot cleaner than they did before, but

the real revelation is the film material. Originally, it looked horrendous (look

at the clips in Taken Out of Time),

but no more. Colours are amazingly vibrant, and from a technical perspective,

it now almost looks as though it could have been filmed yesterday.

More than 30 Years in the TARDIS, on the

other hand, hasn’t been touched from a restoration viewpoint, due to technical

limitations in the way it was shot in the first place. It is taken directly

from BBC Worldwide’s master, and doesn’t look too bad, but darker scenes are a bit noisy and there are occasional

video dropouts throughout. The clips in the documentary are likewise

un-restored, and while some may bemoan this, I personally like to see the state

these episodes were in prior to their DVD releases. (Ordering up all the tapes

of the restored versions would have been a logistical nightmare anyway, not to

mention the many hours that would have been needed to reinstate the clips

frame-accurately.)

SUMMARY

It’s a shame

that Shada is still stuck in its 1992

form, which does feel rather substandard now amid the rest of the DVD range,

but More than 30 Years in the TARDIS

is a stunningly good documentary to this day. The Legacy Collection is one of the strangest DVD releases I’ve

ever seen, primarily because of how miscellaneous it is, but the standard of

the special features is generally very high. This is the starting line

of Doctor Who’s fiftieth anniversary year, and

while it is massively flawed in terms of the presentation of the only story on-board, the documentaries (both new and twenty years old)

are worth the price of admission.

6 OUT OF 10

Buy Doctor Who: The Legacy Collection at BBC Shop

Purchasing this title through either of the links above helps to support this website.

No comments:

Post a Comment